Over the past century, the banking industry has undergone a sea change, and so too has its architecture and design.

Built in 1916 during Winona's waning years as a river port, the towering Egyptian-inspired entry portico displays a monumentality that belies the otherwise diminutive scale of the building. Inside, a gleaming white marbled hall is bathed in daylight. Richly veined green marble planters anchor stair landings and a mezzanine balcony. Stunning Persian blue stained glass and overhead skylights are courtesy of Tiffany Studio, while brass grillwork adorns the two staircases leading to an upper floor gallery of African safari treasures that include, among other since-illegalized booty, a stuffed ostrich and a rhinoceros head.

Built in an era of lofty aspiration and civic high-mindedness, Winona National Bank contrasts sharply with today's community-oriented financial institutions.

Quoted in the 1917 edition of Architectural Record, design architect George Maher touted the ennobling value of his design for the Winona National Bank: "The architecture was to express the idea of service and beauty; the building was to be so arranged and designed as to be of practical and educational value to the community and thus to be in harmony with our democracy and our Americanism."

My own credit union, by contrast, is not a free-standing structure, but a leased space in an office building. Inside, the finishes are on par with many commercial interiors — acoustic ceiling tiles, paint and textured wall coverings on vertical surfaces, and tile and carpeting underfoot. Accents of wood paneling at transaction counters and framed "duck art" contribute to a setting that feels more residential than institutional, more homey than Homeric.

What a difference a century makes.

The point of this comparison, however, is not to bemoan the decline in fabulous bank architecture in America (which is inarguable), but to illustrate how architectural styles and the color palettes associated with them can convey ideas about wealth, trust and social status. Times have changed and so has the banking industry.

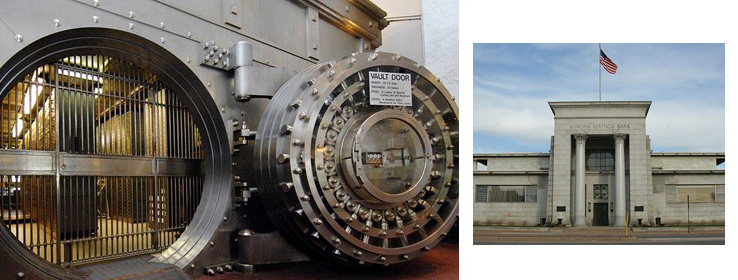

For starters, banks used to be a place where you brought your physical money (and gold bars and diamonds, if you had them) to be placed in a physical vault. If a building looked solid and durable, you probably slept better at night. Like many bank buildings of its day, Winona National is a decorated bunker, with windows raised high above the ground level and public access provided through a single pair of enormous forged metal doors at a highly visible front entry. The bank's show-stopping centerpiece, however, is the vault itself. A major capital investment, the vault door is typically left open during business hours — the better to display the intricately machined inner workings of nickel-plated gears, cogs and locking pins. A truer marriage of technology and art there never was.

While the building's stone and metal construction imply impenetrability, the neoclassical styling of the interior is meant to convey a sense of permanence and connection to a longer tradition. Chosen for their symbolic ties to a classical past, the polished white marble and verdigris accents of the Winona National Bank could have been lifted from a Godward painting — minus the lounging toga-clad virgins. The color accents lean toward saturated jewel tones — sapphire, emerald, royal blue and ruby.

It's easy to dismiss this heavy-handed borrowing from the past as mere nostalgia, but that would be missing the point. Artists and architects working on the American frontier were engaged in a "bring civilization to the wilderness" mission; they yearned to lend a sense of sophistication to the humble settlements popping up along waterways and railroads. The bank, like the courthouse or the opera house, was considered a haven — a place apart and separate from the dusty, gritty reality of life on the frontier.

The design of my local credit union branch follows a broader contemporary trend in banking architecture — to make the customer feel "at home." Today's financial institutions use nostalgia about a simpler time to belie our utter dependence on computer circuitry, satellites and fiber-optic cable networks to keep our money safe. Even as I shift money online between savings and checking accounts at lightning speed, I'm looking at a computer screen with a parchment paper background.

While, as an architect, I may pine for the luster and nobility of a proper neoclassical bank hall, what I get is more akin to the ubiquitous coffee house chain — without the fireplace. Muted earth tones cascade over a relaxed jumble of teller counters, lounge furniture, a welcome desk and walnut-toned cubicle furnishings reserved for middle to upper management — who, by the way, dress the same as their cohorts manning the drive-through windows. Coffee is available in a press pot next to the magazine rack. There is no lofty atrium. No stained glass. Not even a stab at symmetry. Everything is casually arranged and the employees affable. Any hint of a state-of-the-art indestructible metallic vault, or even a lockable drawer, has been erased from view.

As with the banking industry, our architectural expectations have changed to meet societal norms. At the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, people placed trust in those they either feared or revered. Today, we put trust in people that we perceive are most like ourselves. We used to build banks as landmark structures that emulated palaces and temples of the classical era. Today we retrofit leasable commercial property for a "financial services branch" to make people feel comfortable.

Collectively, we discern the difference in propriety between the two environments. The gilded banking halls of the last century are steadily being repurposed as boutique hotel lobbies, fancy restaurants and fashion stores — any operation where "appreciation of the finer things" is written into the business plan. They're too formal for our twenty-first-century, jeans-and-T-shirt approach to opening a checking account.

But maybe this is OK. In the past, banking was reserved for the privileged, and those on their way up the social ladder with something to prove. Today, everyone with a regular paycheck can get a bank account of some sort. We have other (sometimes even better) reasons to dress up and to go someplace extraordinary and grand. Just don't forget to stop by the ATM for some cash.